Preamble

Death and rebirth are central themes of Christianity, both in its mythology—the story of Jesus is about coming back from the dead—and in its actual history. Christianity resurrected dead and dying older traditions and carried them forward into the Middle Ages and beyond.

Three major examples—all readily allegorized by death and rebirth—are debt forgiveness, astronomical cycles, and ego death. These are the three main layers of Christian source material.

The experience of ego death feels precisely like a personal death and rebirth. That’s why existing religions in the Mediterranean Basin held god-eating ceremonies with psychedelic compounds like ergot to induce ego death, preceding the bread and the wine of the Christian Eucharist by a thousand years. The experience of ego death and rebirth found a perfect allegory in ancient stories of resurrected gods.

This essay in one sentence:

In Athenian society, centuries of ritualistic ego death informed the simultaneous inventions of democracy and drama and, a century later, the psychedelic Greek philosophy of Platonism.

System Failure is designed to be shared! If you like what you’re reading, spread the word…

Ego Death

For centuries, the goddess Demeter's grain and the god Dionysus's wine were centerpieces of the two most significant Mystery Schools in the Greco-Roman world. These special menu items were ritualistically eaten and drunk during the sacred meals around which these cults were organized.

Tangible evidence points to psychoactive compounds in these meals. Artifacts used in the rites of Demeter test positive for ergot, while wine casks from the “Villa of the Mysteries” in Pompeii test positive for opium, cannabis, white henbane, and black nightshade. Though definitive proof remains elusive, hard evidence strongly suggests the closely guarded secrets of the Mystery Schools were psychedelic substances.

These substances induce an experience called “ego death”, in which the mental conception of the self is temporarily dissolved. However you regard yourself, that’s your ego. This mental reflection of the physical body is an indispensable evolutionary tool; it‘s how we know which mouth at the dinner table to feed.

Most of us remain convinced that we are our egos because we spend all our waking hours identifying with this mental conception of the self. However, the experience of ego death demonstrates, unintuitively, that a point of view still remains once the ego has been dissolved. It shows us that our egos are not actually essential to our existence. Instead, they’re like masks we can take off and put back on again.

It may be a coincidence that Athenian society invented drama and democracy at the same historical moment that large swathes of the population were ritualistically dissolving their egos. But it would have to be a colossal coincidence, because ego death is conceptually related to both drama and democracy.

Drama & Democracy

The cult of Dionysus was central to the invention of drama in ancient Greece. Tragedy and comedy both originated from those religious rituals. Dionysian worship involved ecstatic celebrations, music, dance, and choral performances called dithyrambs. These were hymns sung by a chorus in honor of Dionysus. According to legend, Thespis was the first actor to step out of the dithyrambic chorus and perform individual dialogue. Eventually, the Athenian Dionysia became a city-wide festival where playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides competed to stage the finest dramas. The Theater of Dionysus, where the very first plays were staged, can still be visited on the south slope of the Acropolis in Athens.

It’s easy to see how ego-dissolution, as ritualistically practiced in the worship of Dionysus, could have given rise to the stage drama. Ego death reveals an astonishing existence beyond the narrow confines of self-identity. Once the ego is perceived as a costume that can be worn or discarded, a logical next step is the idea of an actor who sheds their own persona to adopt someone else’s.

Democracy, too, has obvious parallels in the experience of ego death. The political theory behind democracy is simply that collective decision-making cancels out the influence of any one person’s ego. That way, we arrive at decisions that are beneficial for all, instead of decisions that are beneficial for one person only. The river of history flows in this direction. Over the long haul, the broad historical trend has been the gradual replacement of less democratic forms of government with slightly more democratic ones.

It may be a coincidence that Cleisthenes, who implemented major democratic reforms in Athens around 508 BC, belonged to the Alcmaeonid family, which had strong ties to the cult of Demeter. When the Eleusinian Mysteries became a state-sponsored festival, his grandfather was archon, or chief magistrate. Cleisthenes and many of his fellow Athenians had almost certainly experienced ego death during the rites of Demeter at Eleusis. Thus, chances are excellent that this mystical experience informed their revolutionary new form of government.

Platonism

In the 3rd century, the Greek biographer Diogenes Laertius wrote down the life stories of the most famous Greek philosophers. His third book is all about Plato. Diogenes reports that Plato traveled to Egypt as a young man—with the playwright Euripides—and was initiated into the mystery religion there (most likely the cult of Isis). Since these two Athenians were so keenly interested in foreign mystery religions, it stands to reason that they were also initiated into the wildly popular mystery cults back home.

Euripides went on to write The Bacchae, a powerful exploration of Dionysian worship that remains iconic to this day. Plato arguably became history’s most famous philosopher. In his dialogues, particularly the Phaedo, Symposium, and Phaedrus, he references mystery religions and initiatory experiences.

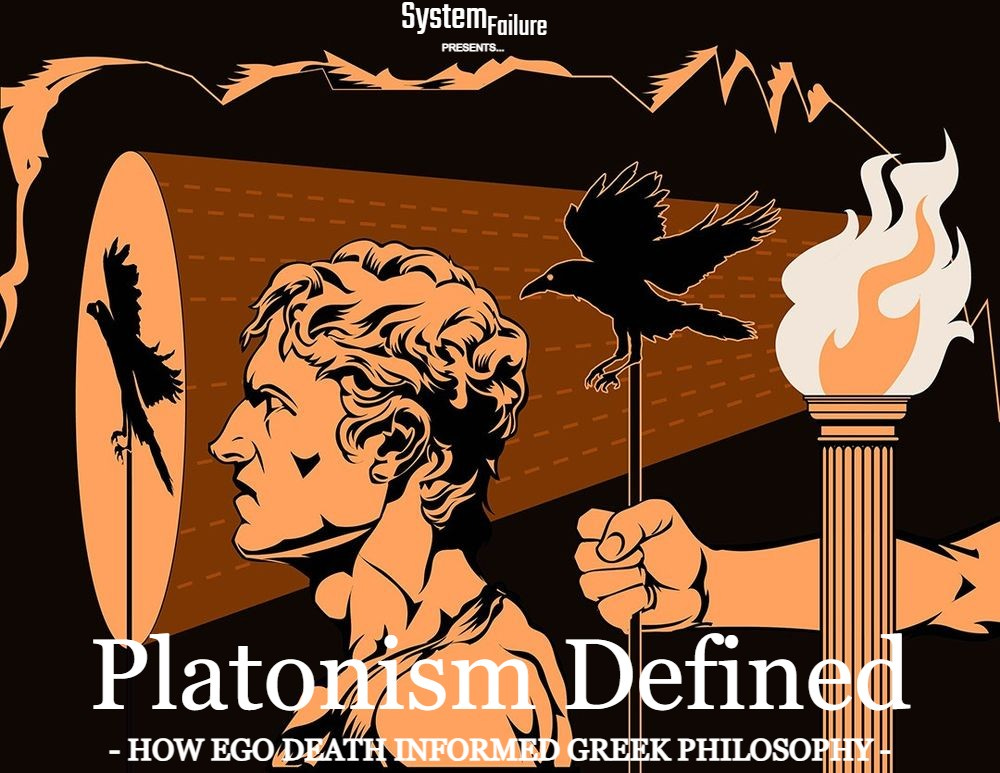

However, the Republic remains Plato’s most celebrated work. In Book VII, he introduces the psychedelic idea that we live inside an illusion. To communicate this groovy notion, Plato paints a vivid allegory in which prisoners are chained to the floor of a cave. They are bound so they cannot move their heads, and unseen puppeteers cast shadows on the only cave wall visible to them. The title card of this essay illustrates the geometry of their unfortunate situation.

In this “Allegory of the Cave”, a prisoner breaks free, discovers the shadow puppet show is an illusion, ascends out of the cave, and emerges blinking into natural sunlight he never knew existed. This, according to Plato, is the journey of the philosopher. But this mystical ascent—from shadows to reality and from illusion to truth—also mirrors precisely the journey of those who underwent ego death in the rites of Demeter and Dionysus.

Plato believed in two realms: the mental realm, where we might decide to clench our hand, and the physical realm, where our hand actually tightens into a fist. He believed that the mental realm is reality, while the physical realm is merely a transitory illusion like the shadows on the wall of his cave.

Plato pointed out that we can only recognize objects in the physical world by referencing an ideal. When you walk into a restaurant, you compare all the objects in your visual field to your preconceived definition of “chair” and sit down on the closest match. Plato would have described that preconceived definition in terms of an “ideal” or the “quintessential” chair.

He noted that physical chairs can come close to the ideal, but they’ll always be slightly imperfect in some way. The ideal chair exists, then, only in our minds, the realm where we decide to clench our hands. That’s why Plato reasoned that this mental realm is the true reality, and that the physical realm—where we actually make fists—is a projection emanating from it. Just as the shadows dancing on the wall of Plato’s cave are the projections of unseen puppeteers.

Platonism is the idea that two realities are arranged in a hierarchy: an imperfect, obvious, transient realm and a perfect, hidden, eternal realm. If that sounds familiar, it’s because these Platonic realms were eventually incorporated into Christianity as heaven and earth.

Further Materials

From that time onward, having reached his twentieth year (so it is said), [Plato] was the pupil of Socrates. When Socrates was gone, he attached himself to Cratylus the Heraclitean, and to Hermogenes who professed the philosophy of Parmenides. Then at the age of twenty-eight, according to Hermodorus, he withdrew to Megara to Euclides, with certain other disciples of Socrates. Next he proceeded to Cyrene on a visit to Theodorus the mathematician, thence to Italy to see the Pythagorean philosophers Philolaus and Eurytus, and thence to Egypt to see those who interpreted the will of the gods; and Euripides is said to have accompanied him thither. There he fell sick and was cured by the priests, who treated him with sea-water, and for this reason he cited the line:

The sea doth wash away all human ills.

Furthermore he said that, according to Homer, beyond all men the Egyptians were skilled in healing. Plato also intended to make the acquaintance of the Magians, but was prevented by the wars in Asia. Having returned to Athens, he lived in the Academy, which is a gymnasium outside the walls, in a grove named after a certain hero, Hecademus, as is stated by Eupolis in his play entitled Shirkers:

In the shady walks of the divine Hecademus.

Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book III